16/09/2020

Economy

IMMUNITISED, HIGH TOUCH, HIGH TRUST: Revive the Thai tourism sustainably by cultivating spatial immunity: Extra service level and build long-term trust

รศ.ดร. นิรมล เสรีสกุล ผศ.คมกริช ธนะเพทย์ อดิศักดิ์ กันทะเมืองลี้ มัญชุชาดา เดชาคนีวงศ์ ธนพร โอวาทวรวรัญญู ปรีชญา นวราช

Asst. Prof. Komkrit Thanapat, Asst. Prof. Dr. Niramon Serisakul, Adisak Kantamuangli, Manchu chada Dechaniwong, Preechaya Nawarat, Thanaporn Owat Worawaranyu

The global economy, tourism and Covid-19

Over the past decades the global tourist sector had been steadily growing. As a result, tourism was one of the fastest growing and largest sectors of the world economy. Tourism helps promote the economy as a whole: Income from tourism was 10.3 percent of the global GPD and created jobs for 1 in 10 people or 330 million people worldwide (WTTC, 2020). Tourism is especially important in developing countries with low economic diversity. Tourism is an industry that does not require specialized skills. Merely opening one’s “house” to tourists can generate significant revenue. Tourism is also an opportunity to create jobs for women, youth and marginalized people. The ‘visa wall reduction policy’ has reduced travel expenses, the comparatively low cost of living in developing countries is an important pull factor for tourists from more advanced economies.

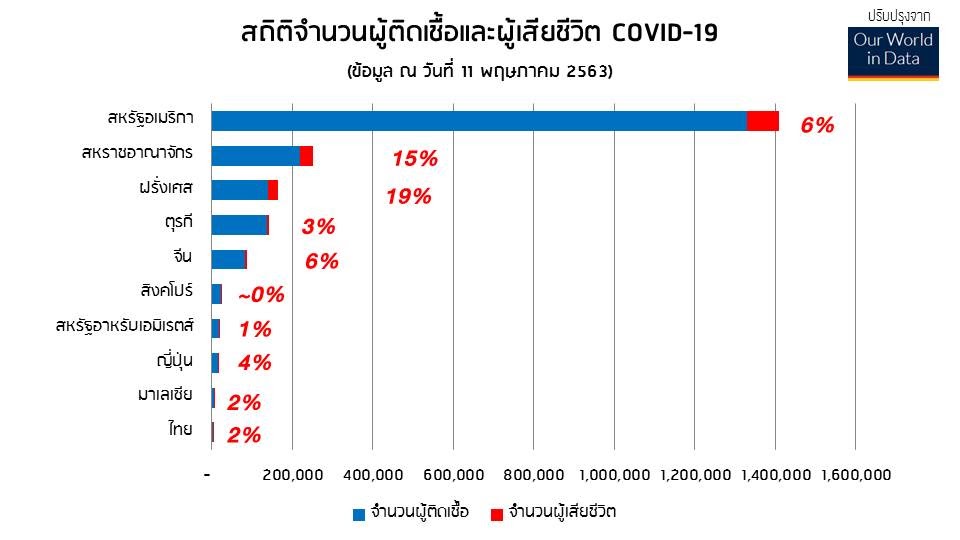

However, since the beginning of 2020, the virtual global lock-down to prevent international transmission of COVID-19 has decimated the tourist industry. Countries banned travel by people from countries with major outbreaks, planes stopped flying, hotels were shuttered, and a multitude of tourist destinations were closed – temporarily or permanently. Thailand in particular has had a heavy dependence on the domestic and international tourism sector, and it is suffering the effects of both the national and global restrictions on movement of people for non-essential travel. COVID-19 has also exposed Thailand’s weakness and vulnerability to a sudden crisis which impacts tourism. Indeed, Thailand can be classified as a “Hyper Tourism Dependency” country which employs tens of thousands of people. While the epidemic in Thailand was never that serious as in some other countries, it may still take many years for tourism to return to the pre-COVID-19 levels, if at all. It is doubly surprising that Thailand has emerged largely unscathed by COVID-19 given that the first case of infection outside of Wuhan, China was in Bangkok. Now, as the Thai government is gradually relaxing the control measures, the Thai tourism sector can begin to mount a comeback.

Adapted from: Our World in Data

In this regard, UNWTO has provided guidelines to help prepare and handle the tourism recovery effort during this crisis. The strategy can be divided into three main areas as follows:

1) Problem Management: Situation control and managing tourism businesses to support themselves and support workers in times of crisis;

2) Stimulating recovery: Issuing policies that promote and stimulate tourism including building trust with the public to stimulate the economic recovery;

3) Prepare for the future: Learn lessons from the current situation to prepare to deal with future problems and create cooperation in tourism development for sustainability.

Thailand has implemented the first two strategies to some extent and is transitioning to strategy 3. This represents a major turning point in the recovery and should be undertaken with caution.

Turning COVID-19 into opportunity: Case Study of Phuket: Global Tourism Destination

The “Pearl of the Andaman” or Phuket Island, is a treasured destination for tourists domestically and from around the world. Phuket has the full range of natural resources and complete services and amenities. Over the decades, travelers have learned to trust the quality and consistency of the tourism experience in Phuket. Each year, Phuket’s tourism income generates a significant amount of revenue for the country. Phuket Province has a gross domestic product of approximately 450 billion baht per year, of which about half is attributed to tourism and related services (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2017).

However, in recent years, Phuket has encountered many challenges that have dampened the tourism situation, as have other provinces of Thailand. Thai tourism policy in the past focused on discrete tourist spots as part of a route that would shunt tourists among connected attractions. However, this routing of tourists was planned separately from the overall design and development guidelines of the province, resulting in a lack of a common direction of the multiple sectors. In addition, the basic infrastructure of the beach towns could not keep pace with the growth in tourism. Without a master plan or external controls, Phuket attracted too many tour operators who were more concerned about short-term profits than sustaining the natural resources that attracted the tourists in the first place. There was also an excessive dependency on migrant labor to perform routine jobs. Over time, these shortcomings started tarnish the image of Phuket and degrade the tourist experience (Aphiwat and Komkrit, 2019). In addition, Phuket faced a crisis of confidence in safety of tourists after the 2018 tour boat sinking and death of scores of Chinese tourists. As the value of Thai baht strengthened on international currency markets, a trip to Phuket was becoming less affordable. Thus, Phuket could never really live up to its tourism potential. In one sense, it could be said that Phuket was caught in a ‘middle-income tourist trap,’ and that in itself was already threatening the sustainability of lucrative tourism even before COVID-19.

Now, with global tourism at a virtual standstill, there are grave doubts about the potential for Phuket to recover to its past glory as a premier tourist destination. Therefore, there needs to be urgent comprehensive planning if tourism is to be revived. That will require both a near-team and long-term vision of what needs to be done and what Phuket’s real potential is. A key intangible factor is restoring trust among tourists that they will enjoy a safe and high-quality experience while on the island.

Source: Department of Tourism Ministry of Tourism and Sports

Short-term planning for the rehabilitation of tourist cities before the new normal sets in

As predicted by the International Air Transport Association, more than 60% of tourists will start to book tickets at least 2 months after the COVID-19 outbreak has been controlled, and another 40% confirm that they will wait at least 6 months later. However, these are very fluid estimates which could change rapidly based on country regulations and perceptions of risk. In any case, Thailand needs to start planning and preparing for the opening-up of its borders and airports to foreign tourists in the coming months. For this work smoothly, all sectors should be actively involved in developing the action plan, and urgently implement the necessary tasks once there is consensus about the way forward. This is indeed a race against time. The number of tourist businesses, large and small, in Phuket is considerable. However, they all have different limitations and constraints in staffing back up and restoring operations after a virtual lock-down situation that lasted for months. Thus, it is imperative to accelerate the planning and implementation of recovery, lest the economic downturn feeds on itself.

Social distancing is not enough to re-open a tourism city after Covid-19

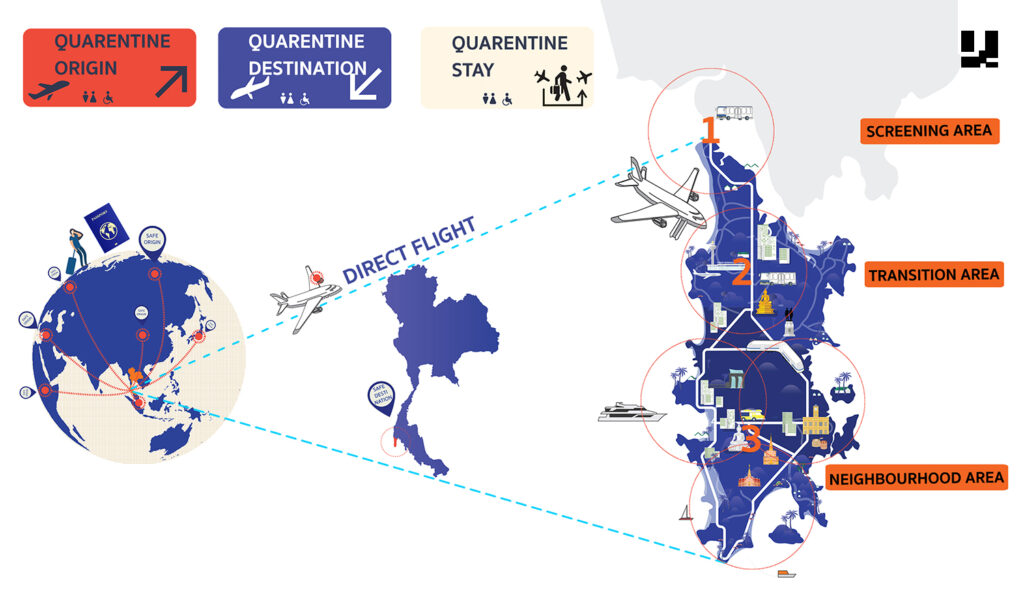

Reducing crowding along will not be enough for the full restoration of the tourism business while the threat of Covid-19 remains. Indeed, there are certain economies of scale in the mass tourism business that requires strangers to travel and lodge in the same transport and accommodations. Thus, there is a need for a paradigm shift to approach tourism in the context of a pandemic. In other words, why not design an approach to tourism which is a public health intervention at the same time. The target audience would shift from the carefree tourist to the more health-conscious traveler. In addition, Phuket could be positioned as the ideal place to practice self-isolation during periods of containment. Phuket could be re-branded as a sanctuary and ultra-safe temporary residence in a tropical paradise. This would involved creating what might be called an “Immunitised Community” by using three main strategies as follows:

1) Marketing and branding the city as a sterile area. This will attract tourists who are willing to spend a longer time during their tourist visit to reduce the psychological impact of the 14-day detention program.

2) Manage infection control from the point of origin and destination of the trip, including a “travel bubble” in which the tourists incur no exposure to Covid throughout the trip.

3) Create an enclosed tourist environment where every visitor is confident that every other visitor, as well as local staff, are free of disease. In this respect, the tourism experience is persuading the visitor to think more like a member of the indigenous community – initially for the short-term, but perhaps indefinitely.

In order to successfully implement the strategy, measures must be taken systematically in 8 steps from the beginning of the trip to the destination, as follows:

1. Aseptic travelers seeking the opportunity of long-term rest

This measure is to providing a unique opportunity for tourists to be disease (i.e., COVID-19) free from a safe point of embarking, straight to the destination (i.e., no exposed transit in any stops along the way). Travelers would carry a “Digital Health Passport” to confirm their status and instill confidence in others that all tourists coming to the same destination will not introduce pathogens. Therefore, this step will require cooperation of the government of the country of origin to issue the Digital Health Passport.

2. Online platform for safe tourism

Another issue to bear in mind in tandem with the adjustments to the physical design is the implementation of international public health measures, i.e., inspection and quality control. This would involve the creation of online platforms for tourism outlets and operators to register – provided they meet the stated public health standards. That would build confidence for both tourists and service providers. The platform would encourage tourists to be more self-reliant and remain in the province for longer stays. Conversely, the high-turnover, short-stay group tourist format would be discouraged as another strategy to reduce potential introduction of the virus. The platform would provide information on travel routes, tourism service points, and public health service points, and include an online travel booking system. This would help create an appropriate tourist distribution system, both in terms of timing and location. The online platform would provide real-time information and publicize participating retailers, services, and amenities to reach a wide range of potential tourists.

3. The international airport: The first portal to Phuket

The Phuket International Airport is the most popular gateway to the island. However, as the first port of air entry, there needs to be an efficient and strict system for screening passengers which complies with international public health standards. There would need to be density control and social distancing at luggage collection points, ticket check points, and seating in the boarding areas, just as some obvious examples. Passengers would be divided into zones to ensure manageable distribution and transit. In addition, the airlines which fly to Phuket would comply with disease control measures to prevent any possibility of exposure to pathogens during the flight. Intelligent airport design models such as Singapore’s Changi International Terminal 4 may be considered as a way to think about terminal expansion in Thailand going forward.

4. Quarantine areas as a place for quality rest and relaxation

The whole concept of confinement during the COVID-19 incubation period could be transformed into a version of two weeks of R&R: rest and recuperation. Phuket has the immediate advantage of being an island, with only one land connection to the rest of Thailand. Further, Phuket International Airport is located 20 kms from the provincial urban center, and that makes it easier to arrange the screening and confinement zones than it would be for other provinces with airports near urban centers or tourism destinations. This step requires coordination and collaboration between the government and entrepreneurs with lodging within proximity of the airport and the world-class beaches which Phuket has to offer. The recommended two weeks of self-imposed confinement presents an opportunity for hotels with low levels of occupancy to be converted into holding areas for these travelers. This could be portrayed as a marketing pitch to attract the cautious tourist.

5. Safe travel network

Traveling puts the tourist at inherently higher risk of infection and transmission due to the need to encounter diverse collections of other travelers, and often having to be conveyed in forms of transportation that require some degree of crowding in order to be economically viable. Often, those conveyers have closed air systems, and that further puts the traveler at risk of sharing airspace with an infected person who is shedding virus with each exhaled breath. Thus, as much as possible, transit points and people-movers need to have adequate ventilation and air quality, with queuing which meets social distancing guidelines. Some waiting areas or transportation may include partitions between seats to allow for denser seating arrangements. The Department of Land Transport would need to issue guidance for this so that practices are standardized throughout the province and the Thailand as a whole. After each transit journey, the vehicles would have to be sanitized due to the ability of the virus to remain infectious on surfaces for hours. There should also be an online traffic network display system so that tourists can know in real-time when a transit vehicle will arrive, locations of embarkation and disembarkation, and the ability to reserve seating and make payments for transit online.

6. Safe lodging as an essential enhancement in the new paradigm of a pathogen-free strategy

Places for overnight lodging need to comply with WHO Operational Considerations for COVID-19 Management in the Accommodations Sector, and these considerations are summarized as follows:

• Physical design: This dimension focuses on the allocation and systemization of the reception area and the hotel common area which now need to have screening stations, and places to decontaminate using advanced cleaning and sanitizing procedures according to international standards. People may need to pass through these stations many times a day, and there needs to be open re-ventilation every two hours. In addition, there needs to be a cleaning schedule for the hotel room or accommodations appropriate to the allocation of guest rooms to allow enough time to kill germs and air the room out for proper ventilation.

• System engineering, ventilation and sanitation: There should be a thorough examination of the effectiveness of use of ventilation and hygiene measures to ensure that the cleanliness standards apply to the entire hotel staff, in addition to the physical enhancements.

• Basic hotel services: Hotels should avoid buffet meals or parties during an epidemic. However, if this cannot be avoided, then an advanced cleaning system should be applied before and after the event. There need to be controls for density of participants, ventilation, and special attention paid to shared containers which need to be replaced regularly. The social distancing guidelines apply to those waiting or sitting in the event area. Generally, one table can accommodate a maximum of four people (for ten square meters), with the distance around each chair of at least one meter in all directions. Playgrounds should be closed during an epidemic due to the potential vulnerability of young children.

Apart from these measures, a key element of the paradigm shift for hotels and accommodations in the post-COVID era is that the tourism sector must shift from large-group events to a focus on a smaller number of users, and higher-quality tourists who stay for longer periods of time. This will require providing a greater variety of tourism experiences, eco-tourism, and contact with nature and the local environment which places a greater emphasis on the initiative of the individual tourist.

7. Adequate health measures which meet or exceed international standards

Public health services are a central component of the comprehensive provincial development plan. One indicator is distribution of health outlets which stipulates that everyone in the province is at least within 2.5 kms from a health center and five kms from a hospital. The traffic system needs to be designed to accommodate efficient movement of emergency vehicles to/from a clinical care facility.

8. Creating a network and standard practices of local entrepreneurs, with connections to the government and private sector

Tourist cities/provinces are different from other entities. That is because the tourism destination is selling an experience. Therefore, there need to be measures and operations to reduce obstacles and factors that might result in an adverse experience for the tourist. This requires collaboration among all stakeholders in all sectors, including lodging, accommodations, food, transportation, and entertainment. These must be under local supervision to ensure compliance with public health measures at all times. There should be a network of stakeholders, establishment of a database of entrepreneurs, and joint lessons learned meetings in order to help support and participate in other strategies in the future.

The golden opportunity to revive long-term tourism as a sustainable sector of the economy

From short-term action to create an enclosed area for pathogen-free tourism, to long-term planning for a sustainable tourism sector, we need to reconsider the capacity of the tourism resources of the province, which is central to achieving the vision. Over many decades, Phuket’s natural resources were plundered for the sake of expanding the tourism infrastructure, without realizing that it was those resources which attracted the tourists in the first place. Now, there is greater awareness of the value of eco-tourism and the need to return those areas that can be rehabilitated to their natural state. Ironically, the overnight shut-down on tourism in Phuket due to COVID-19 helped to show the benefits of quality tourism as opposed to the mass tour package variety which was gaining momentum. The pandemic is now forcing planners to adopt a new perspective and identify solutions to prevail over the middle-income tourism trap.

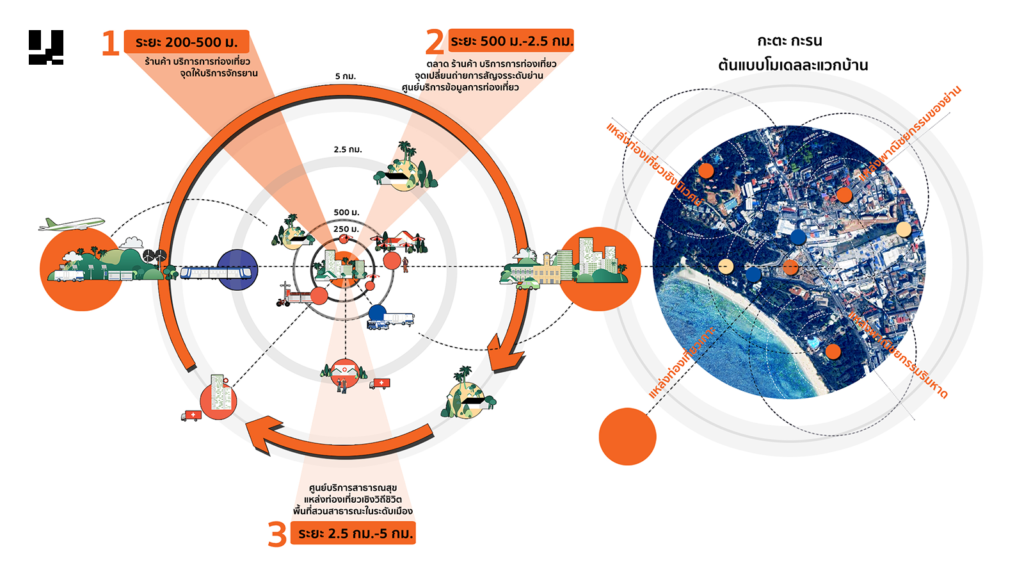

This paper outlines a proposal for a prototype experiment of long-term tourism planning through consideration of the sustainability dimension of tourism. The concept is extracted from ARUP’s research and development in order to define the City Resilience Index (CRI) across the four dimensions of health management, socio-economic condition, infrastructure, and the ecosystem. The CRI is one tool which planners can use to reduce the risk of climate change, coupled with the design of physical planning to accommodate new modes of tourism which are resilient to any future pandemic that may strike. This approach is based on the concept of the density distribution of tourism service areas from urban areas of Phuket to other areas of the island-province. The authors use the case of Kata and Karon beach neighborhoods as a prototype pilot sites. The selection of these areas was made according to the following four selection criteria:

1. Location strategy with the creation of an enclosed area: The Kata-Karon extended coastal neighborhood is a quasi-urban area that exists as an “island” within Phuket Island, surrounded by large hills which provide a natural physical barrier to other parts of the province. Entry and exit to Kata-Karon can be easily controlled since there is a limited road network which winds its way across the hillside. Thus, during an epidemic, this semi-enclosed area is ideally suited to screening visitors, while providing an idyllic location to “shelter in place.”

2. Comprehensive nature sanctuary: These two neighborhoods are actually extensions of each other along the north-south axis of Phuket’s western coastline. Seen from the “Viewpoint” rest area, the two communities are nestled along glorious beachfront, stretching many kilometers. The Kata-Karon nexus consists of ten natural attractions, two cultural tourist sites and two large public parks, namely Karon Park and Khlong Bang Lang Public Park. As a whole, Kata-Karon is an ideal ecotourism destination with a clear target audience of premium quality tourists who are seeking a long-term vacation.

3. The ability to accommodate tourists: Karon Beach alone is over three km in length, and is host to over 300 hotels and 72 entertainment and recreation service establishments. Unlike other tourism sites in Thailand, Karon-Kata has maintained a steady average density of tourists each year, and that keeps the area generally balanced between nature and infrastructure.

4. Advocacy by local partners: There is already in place a grassroots collaboration management system which is comprehensive and efficient, and which operates through effective collaboration among the government, private sector, small and large hotel operators, small-scale service sector, and education sector. Kata-Karon is a living example of deliberative planning among all stakeholders.

Kata-Karon Model Prototype: Creating an “Immunitised Community”

As conceived here, the Kata-Karon Model is an adaptation of premium tourism for the ‘new normal’ in the post-COVID era. The extended area can be envisioned as a health tourism sanctuary or “Immunitised Community.” The Model is design-friendly at two levels: Long-term stays, which give priority to self-contained living; and Inclusivity by upgrading the standards to exceed the international minimums for short-term stays. The design of utilities/amenities is mindful of the need to minimize encroachment on the natural environment and maximize the eco-friendly attributes of the area. The following section outlines the five areas of up-grades envisioned by the design:

1. Creation of a diversity of zones and mixed-use locations to engage a range of interests: The design envisions four levels of zones which extend out from the lodging. These include the 200-250 meters from the lodging which should have convenience stores, food shops, dry goods outlets, and an information/resource center. There would be stands for bicycle rentals or sharing. Extending beyond, to a distance of 400-500 meters from the lodging, there would be a public park or garden, with transit vehicle stops to serve transport needs within and outside the neighborhood. Tourists need a variety of travel options in addition to walking. At a distance of 800 meters from the lodging, there would be additional tourist attractions and services. Studies have shown that, on average, 800 meters is the maximum distance that Thais will walk to reach a transit station or amenities, or about a duration of the ten minutes (GoodWalk, 2015). The facilities within this 800-meter radius should create a “sense of place” by conforming to distinctive design guidelines. As theorized, that uniqueness will motivate the tourist to stay longer. The fact that the tourist can access essential goods and services easily by foot or bicycle should enhance the feeling of being a member of the community.

2. Creation of tourism experience through walking and cycling: The design envisions a transit network which can accommodate all transportation needs of tourists and residents alike. An individual should feel comfortable traveling by him/herself independently by foot or bicycle, to do marketing, visiting a tourist destination, or going to a tourist service center. This network will reduce the need to rely on public transport which carries its own set of risks, or tourist buses. Instead, a system which can be navigated independently by individuals or couples enables a wider distribution of tourists by time and place throughout the area. This independence should create a stronger relationship between the tourist and the host community. The transit network should be designed to link lodging, services, and comprehensive eco-tourist destinations.

3. Public health services which have adequate coverage and standard quality: Karon Sub-district has one community health center, two public health centers, and 13 stand-alone clinics. However, the nearest hospital (Chalong Hospital) is over seven kms away. Thus, if the Kata-Karon community is to meet international standards for health and safety, there needs to be the establishment of a fully-equipped hospital within five kms of the center of the neighborhood. What is more, such a clinical facility should have a premium level of services which are attractive to an international clientele of means, as well as serving local residents. Such a facility would also have specialists on staff and bi-lingual personnel given the significant number of non-Thai speaking clients. This small hospital would be linked to the network of larger international hospitals in Phuket Province.

4. A new strategy for collaborative tourism promotion: The Model envisions a constant flow of longer-term, premium tourists who should be viewed as temporary residents of the locality. Especially in times of international crisis, there would need to be close coordination among hotels, restaurants, and public transport to provide room service to guests who are in confinement. Alternatively, a safe zone could be created within the hotel which meets quarantine standards and reduces self-isolation or crowding in restaurants. This would add value for the tourist experience in difficult circumstances.

5. Control, supervision, and training of personnel: Human resources are, of course, a critical component of the tourism sector. Thus, there needs to be a quality control system and regular refresher training for service personnel, especially those who have to interact with international tourists. Service must always be on-time and up to global standards. Training would also be extended to the staff of local agencies and entrepreneurs to help them prepare for unanticipated situations and uncertainty, with both short- and long-term effects.

In any event, there is no denying that after the COVID-19 crisis has abated, tourism will be changed significantly. If there is any return to a pre-COVID situation, that will not happen for at least two to three years, and only if there is a vaccine and/or effective therapy. The psychological impact of COVID will certainly persist long after the threat of disease has declined to trace or seasonal levels. In addition, there will likely be changes in the preferences and needs of tourists. There will be an increased premium on safety, hygiene, and cleanliness. However, the most important thing is whether planners and managers in the tourism sector draw the correct lessons from the COVID pandemic. Only then will they be able to prepare for the next crisis and a future of uncertainty. The response to the challenge does not end with a new design or strategy as outlined in this paper. Instead, there need to be structural changes that look beyond short-term fixes or adaptations. Tourism managers will always need to have a Plan B, ready at-hand, since it is impossible to predict what the next crisis will be or when it will strike.

In the case of Phuket, as one of Thailand’s premier tourism magnets, the province can use this experience with COVID-19 to design an even more resilient tourism sector while the country and, indeed, the world is waiting to re-open.

The authors are most grateful for those agencies and individuals in Phuket who shared data and ideas, notably, Khun Karn Prachumpan, Chairman of the Board, K.W. Plaza Co., and Khun Manosith Jangjope, President of the Lodging and Boutique Association of Phuket Province.

References

– Apiwat Ratanaworaha, Komkrit Tanaphat. (2019). Final Report: Guidelines for the design and development of tourism in Thailand 4.0: Case Study of Phuket, Chiang Rai, and Pattalung. Bangkok. Office of the Department of Research Support.

– Mingsan Khaosa-at. (2019). Phuket and the Middle-Income Trap Revisited. Accessed at www.bangkokbiznews.com: https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/blog/detail/647197

– Operational considerations for COVID-19 management in the accommodation sector: Interim guidance. WHO/2019-nCoV/Hotels/2020.1

– Phuket Provincial Office (2019). Viewpoint and Values of Phuket Province. Accessed atwww.phuket.go.th: http://www.phuket.go.th/webpk/contents.php?str=introduce_vision

– Office of Policy and Planning of Natural Resources. (2013).

– National Economic and Social Development Council. (2017). Gross Product: Regions and Provinces. Accessed at www.nesdb.go.th: http://www.nesdb.go.th/main.php?filename=gross_regional

– https://kasikornresearch.com/th/analysis/k-social-media/Pages/COVID-19-World- Tourism.aspx

– https://siamrath.co.th/n/146002

-https://www.bbc.com/thai/thailand-52210228

– https://www.pptvhd36.com/news/%E0%B8%9B%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B0%E0%B9%80

%E0%B8%94%E0%B9%87%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%A3%E0%B9%89%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%99/123928

– https://www.bbc.com/thai/international-52521899

– Sharifi A, Yamagata Y.(2018). Resilience-Oriented Urban Planning. Retrieved 8 May 2020 Accessed at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323281125_Resilience-Oriented_Urban_Planning

– Soofi Y.(2016). Achieving Urban Resilience: Through Urban Design and Planning Principles. Retrieved 8 May 2020 Accessed at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315676074_Achieving_Urban_Resilience_Through_Urban_Design_and_Planning_Principles

– https://adaddictth.com/news/7-New-Normal-Mindshare?fbclid=IwAR3ETd5yI1bk9jd3J4Tnb3yYwragKl68qepfGNyt8Wwa7eGKWSHIoB44OQA

– UNWTO. (1 APR 2020). UNWTO LAUNCHES A CALL FOR ACTION FOR TOURISM’S COVID-19 MITIGATION AND RECOVERY. Accessed at UNWTO: https://www.unwto.org/news/unwto-launches-a-call-for-action-for-tourisms-covid-19-mitigation-and-recovery

– WTTC. (2020). The World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) represents the Travel & Tourism sector globally. Accessed at WTTC: https://wttc.org/en-gb/

– National Economic and Social Development Council. (2017). Gross Product: Regions and Provinces. Accessed at www.nesdb.go.th: http://www.nesdb.go.th/main.php?filename=gross_regional

– http://www.goodwalk.org/